Below is the text of a 2017 research write up of the project for EleVR, a reseach and Development Team at SAP

Making the Bed is a VR space developed in Anyland. When it first loads you are plopped down on a red rug surrounded by a cloud of miniature beds. Each bed, in this frozen avalanche of doll furniture is numbered, 1 – 50, and some have a little green dot over the number. That dot is there to indicate which beds you can visit and experience at full size. As stated in the instructions it’s best experienced seated on the floor with a pillow near by so that you can lay down in the full sized versions. Touch a number with the model of your out stretched pointer finger, number 18 say, and you are teleported to a life sized cot in a jail cell. Touch the number again to return home. Touch number 24 and you are teleported to a nest of pillows on a fire escape. Touch the number again to return home.

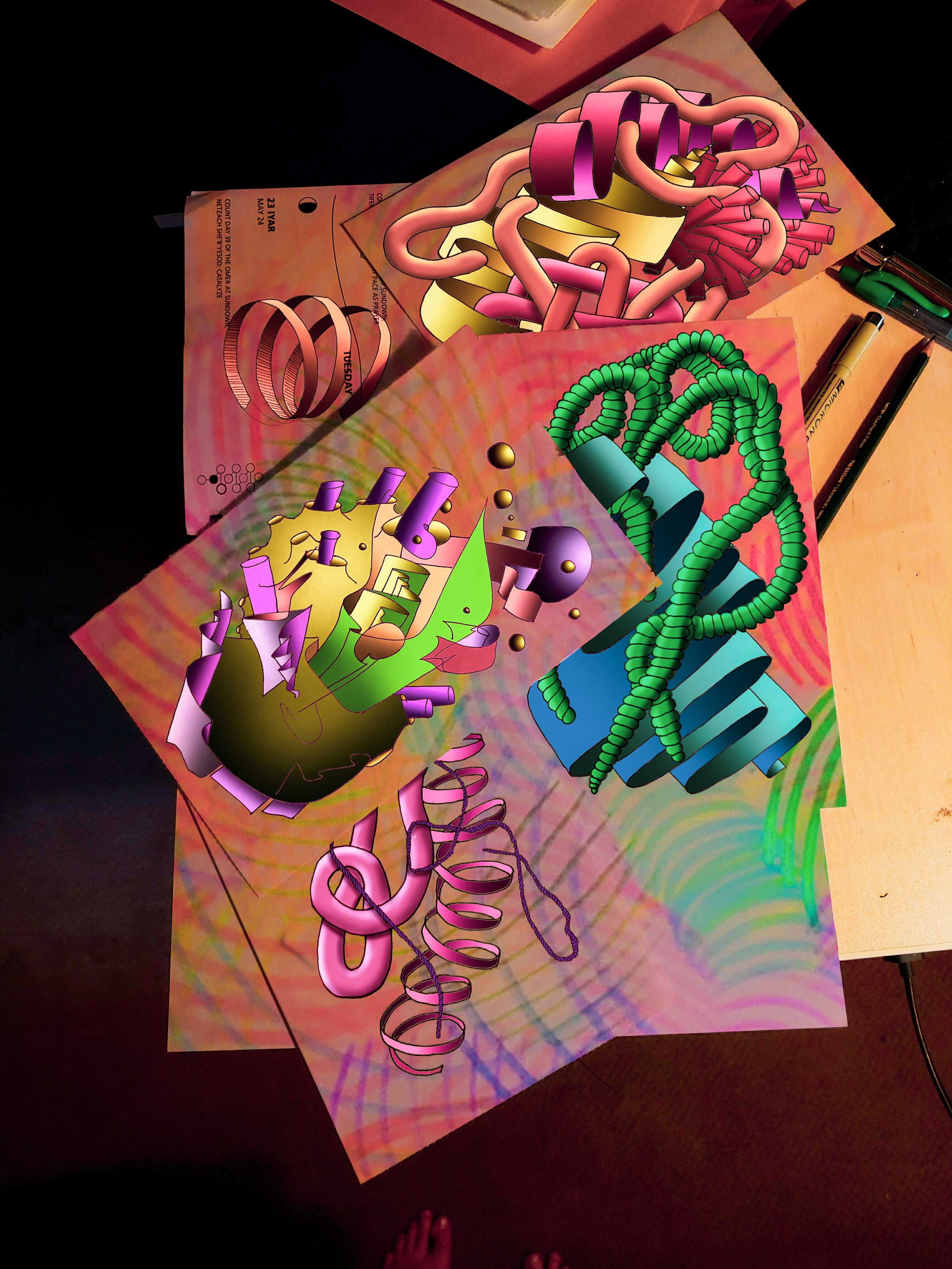

This exploration was sparked by a recent Year of the Body related discussion we had in which Evelyn mentioned an art school course she took called the Drawing Marathon which helped her shift drawing from a mentally directed activity (one of planning and judging) to a physically directed activity (one of arms and fingers making decisions). The class asked her to draw for 100 hours: 10 hours a day, 5 days a week, for 2 weeks. The assignments changed frequently: Draw for 30 mins, now erase everything you drew. Fill larger and larger surfaces. Draw for 30 mins, now tear your drawing into tiny pieces and glue it onto another sheet. Draw the same thing, a piece of fruit for example, 50 times.

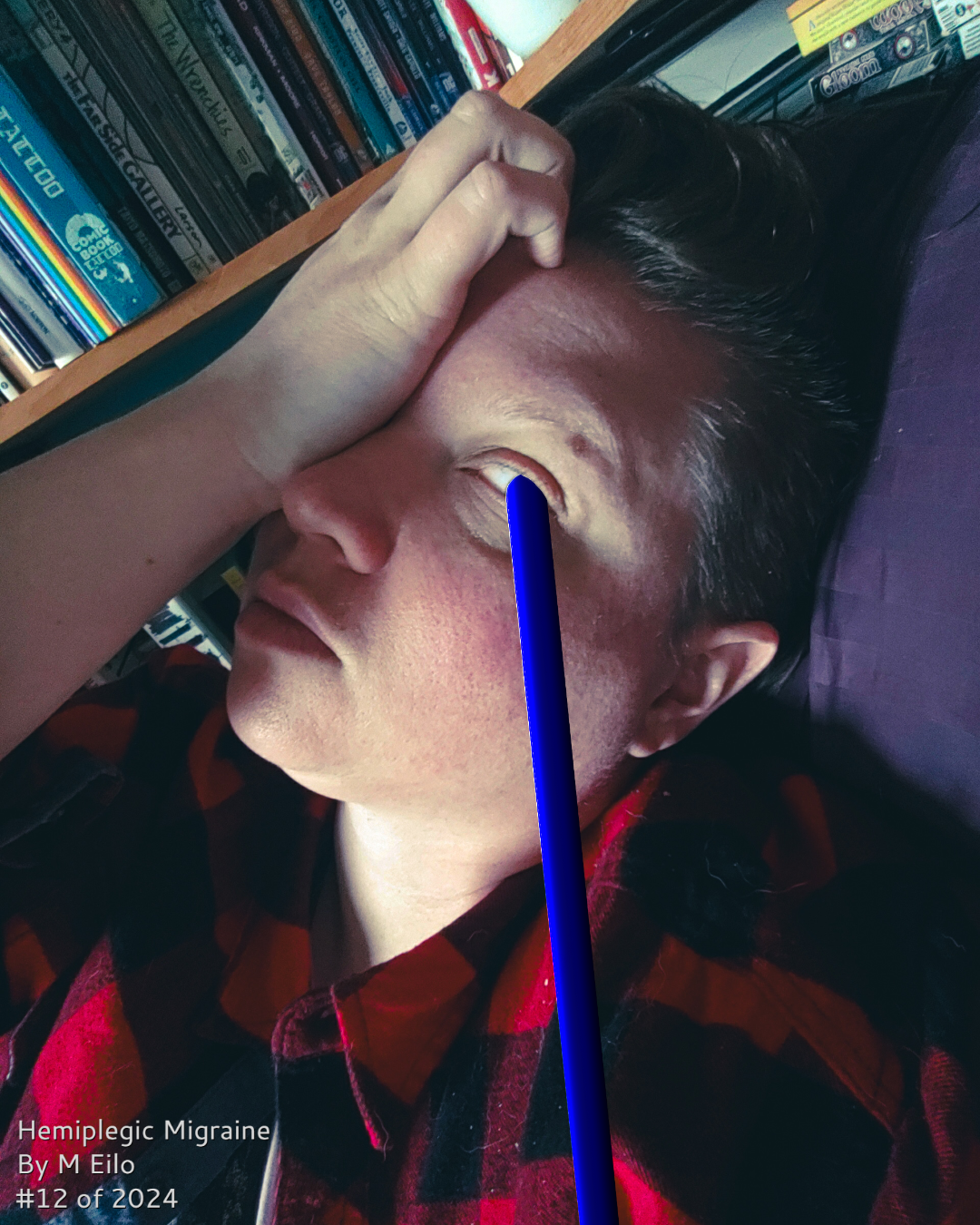

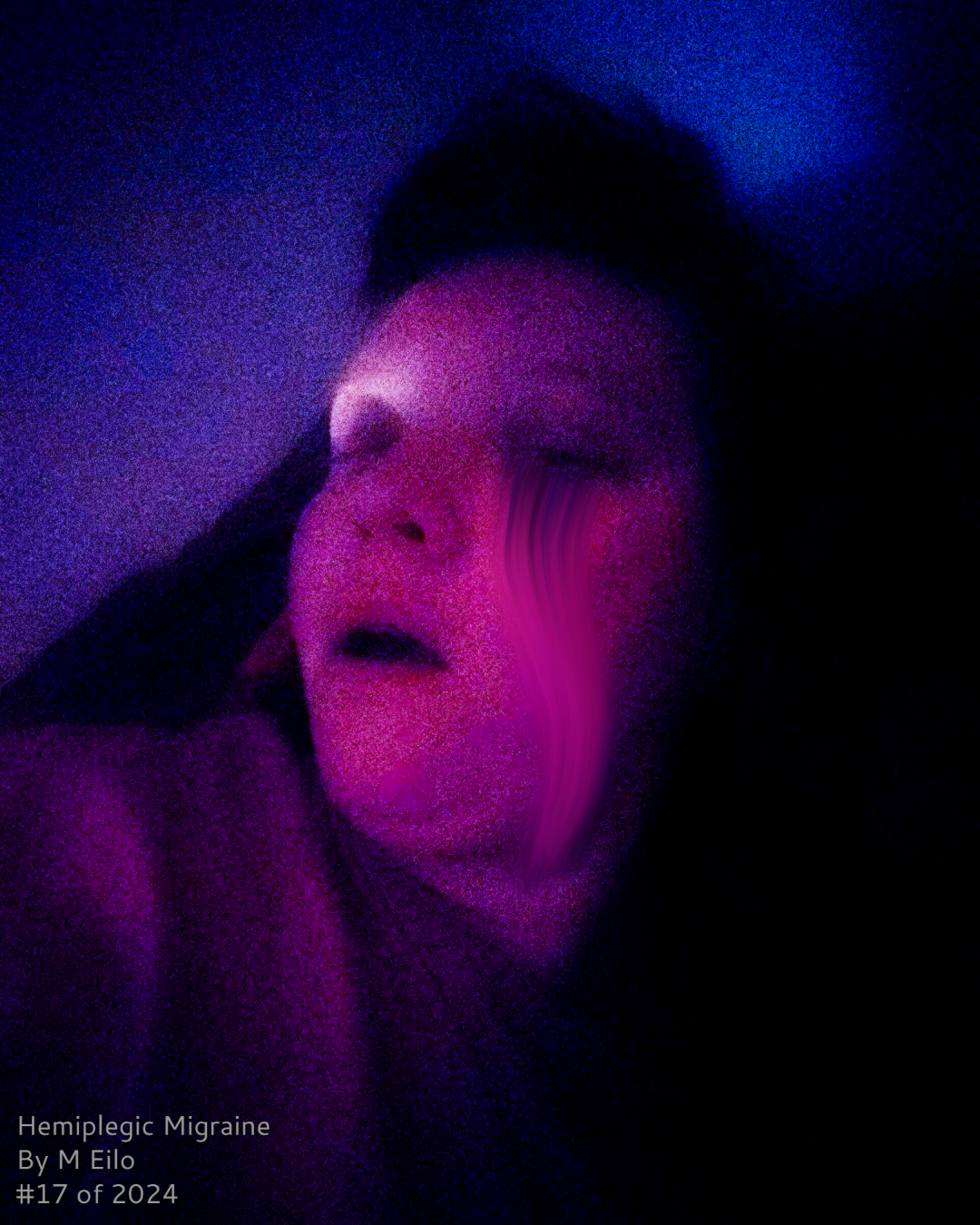

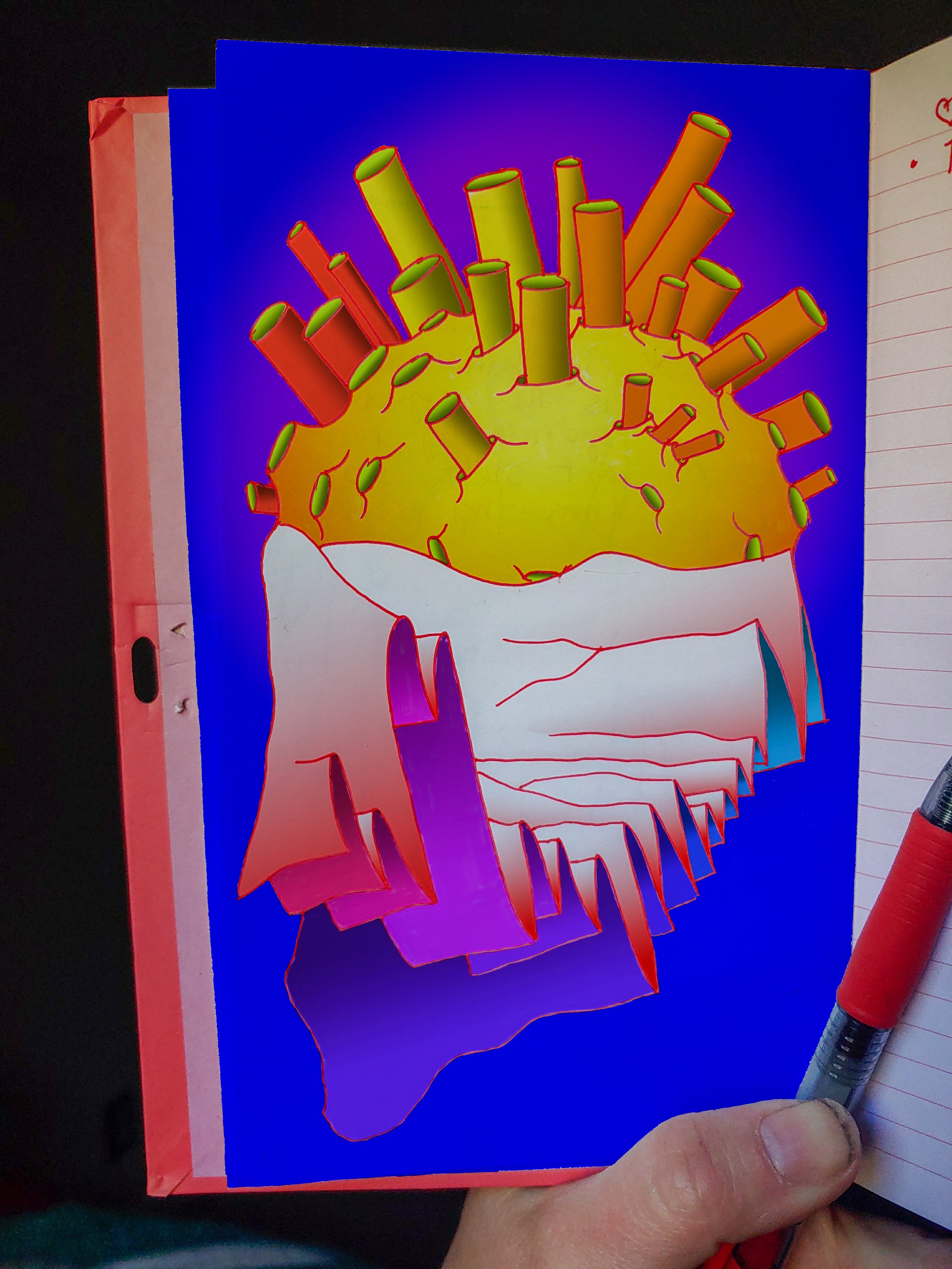

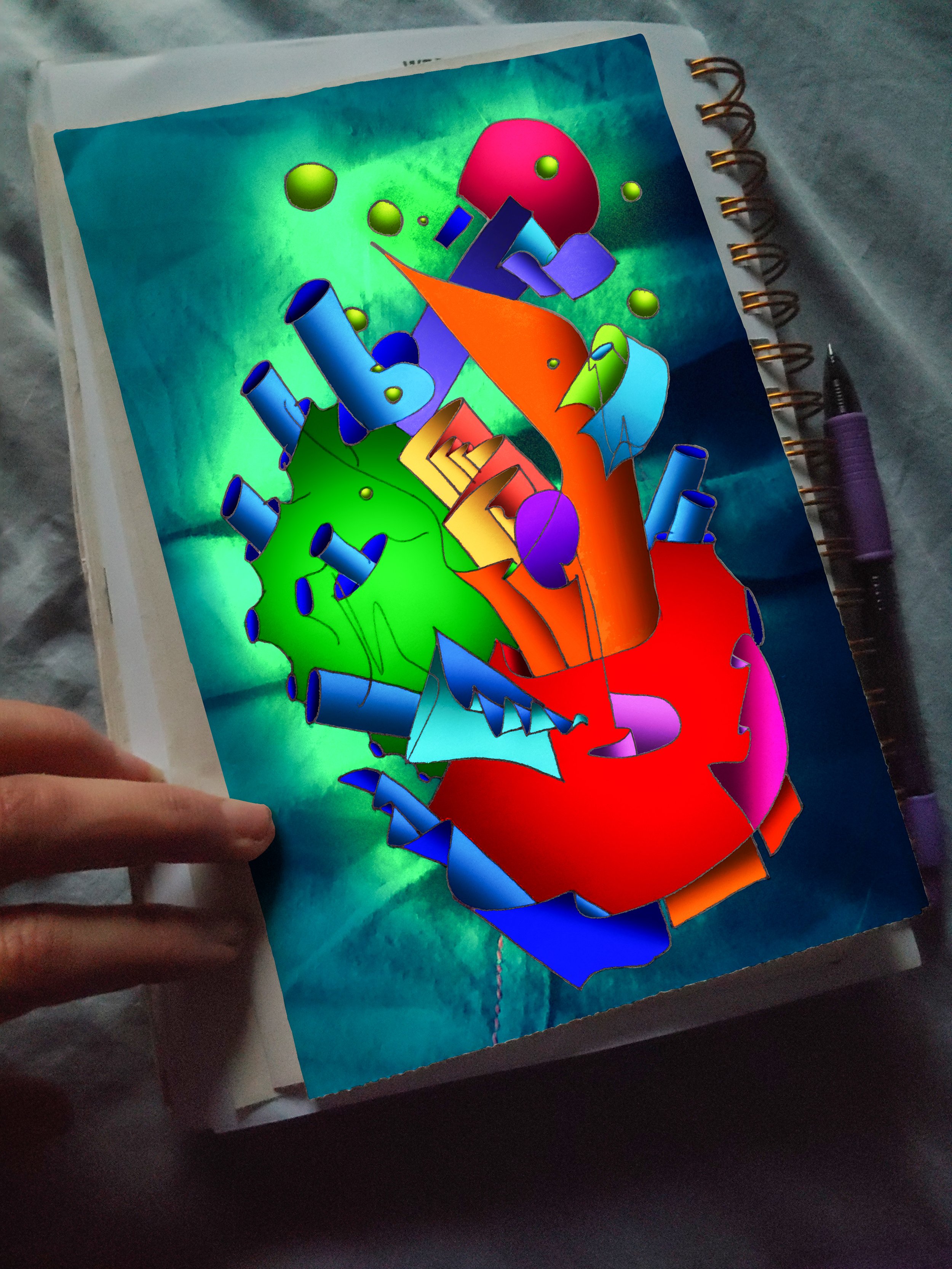

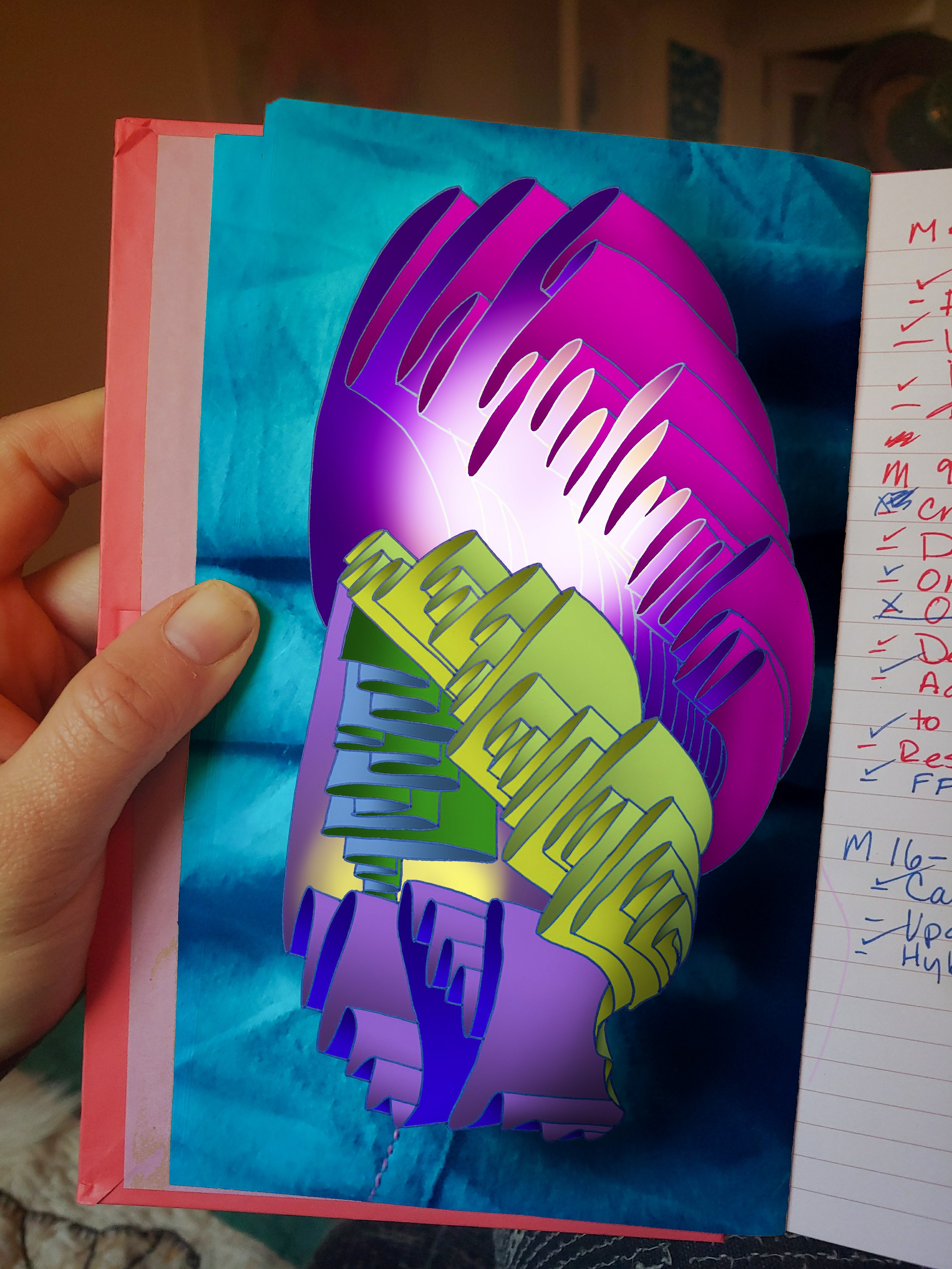

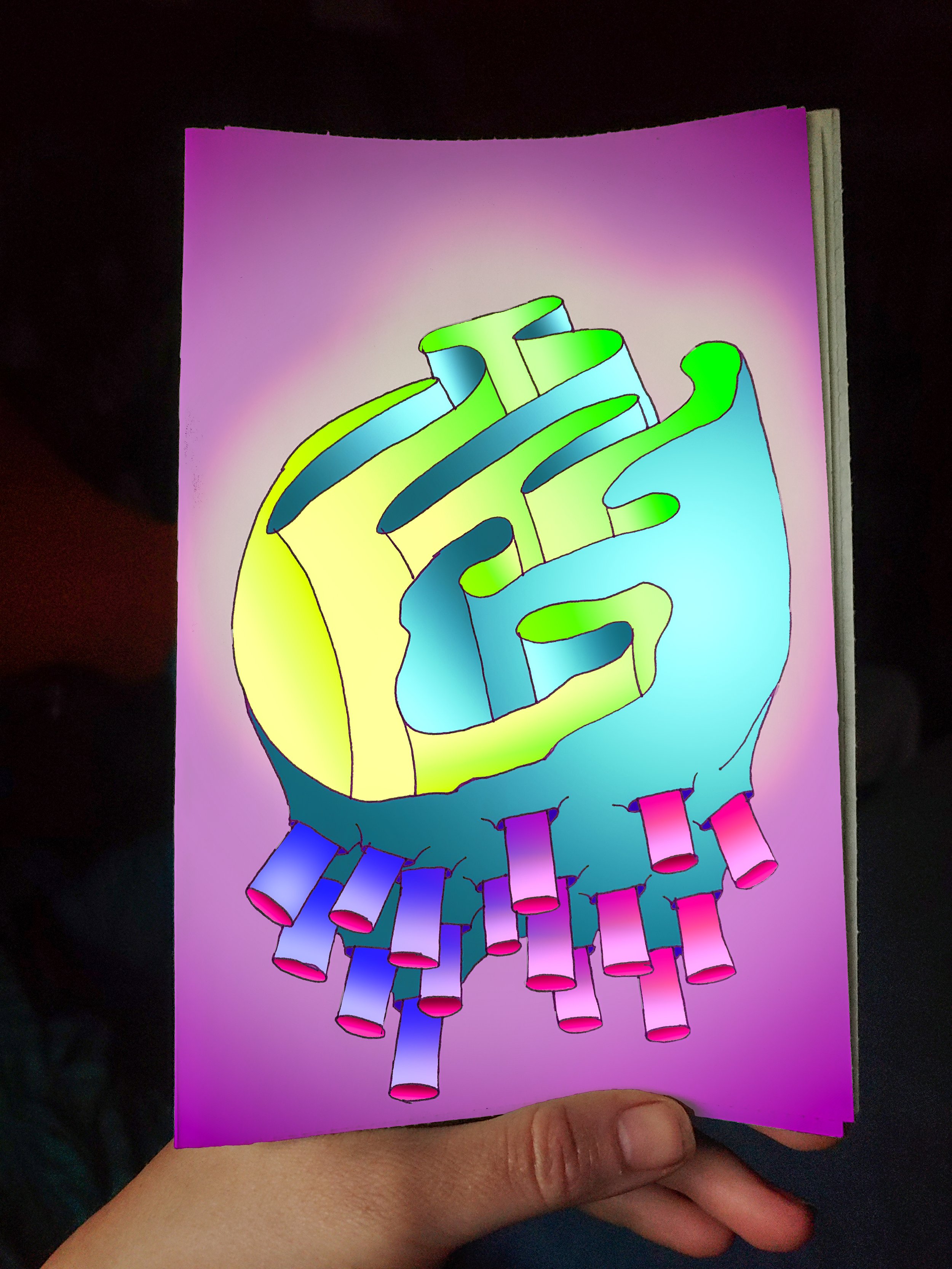

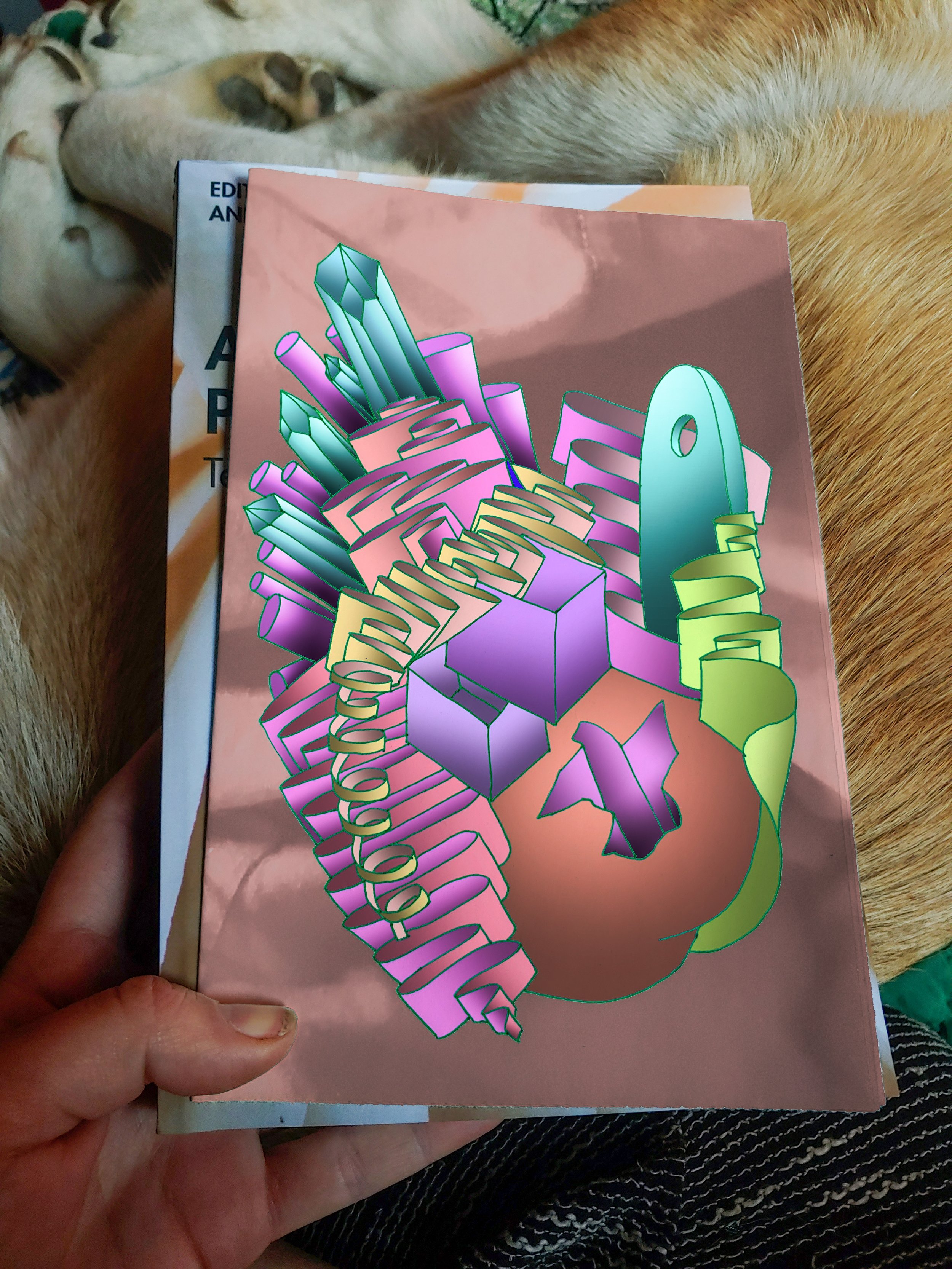

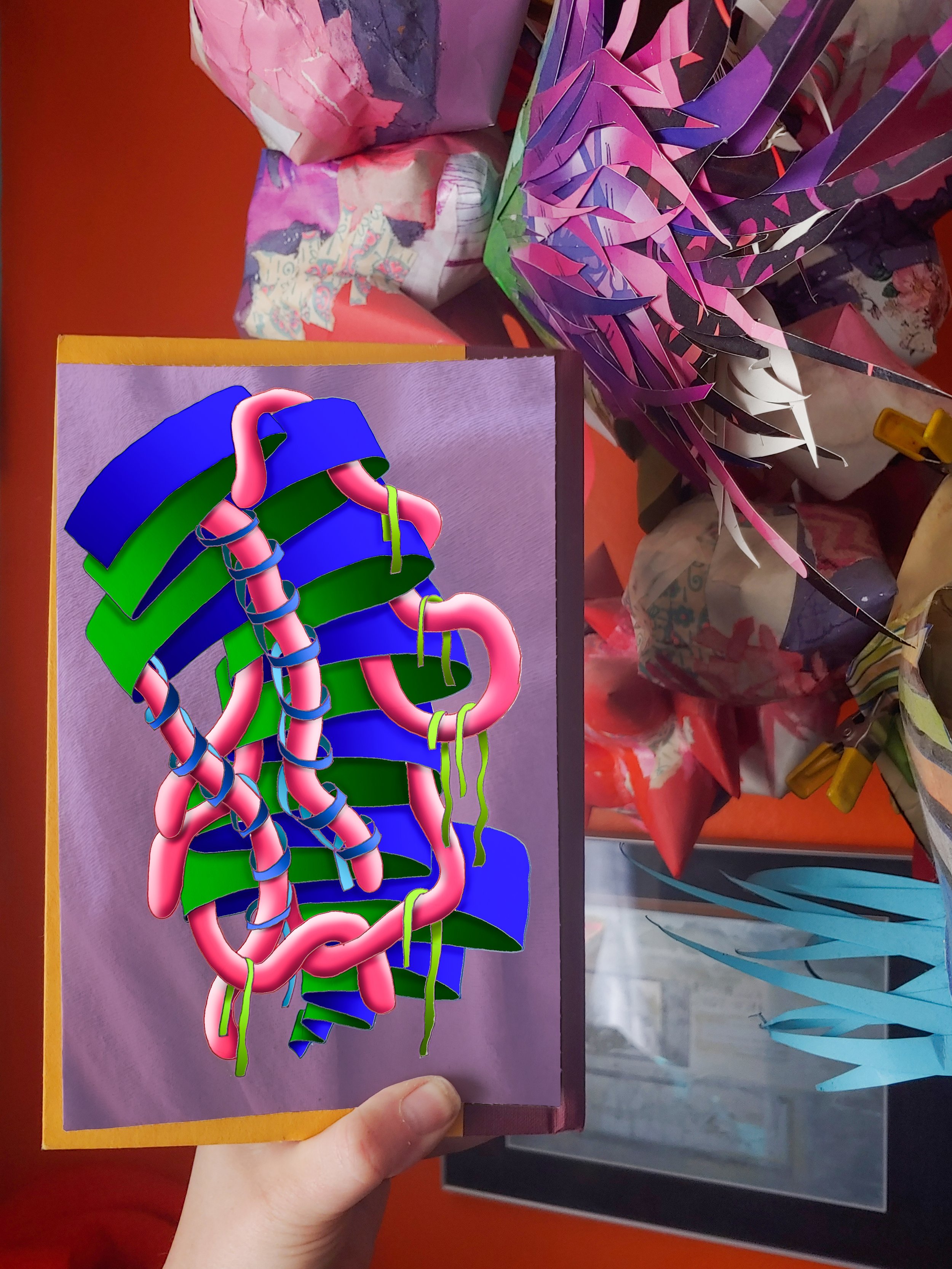

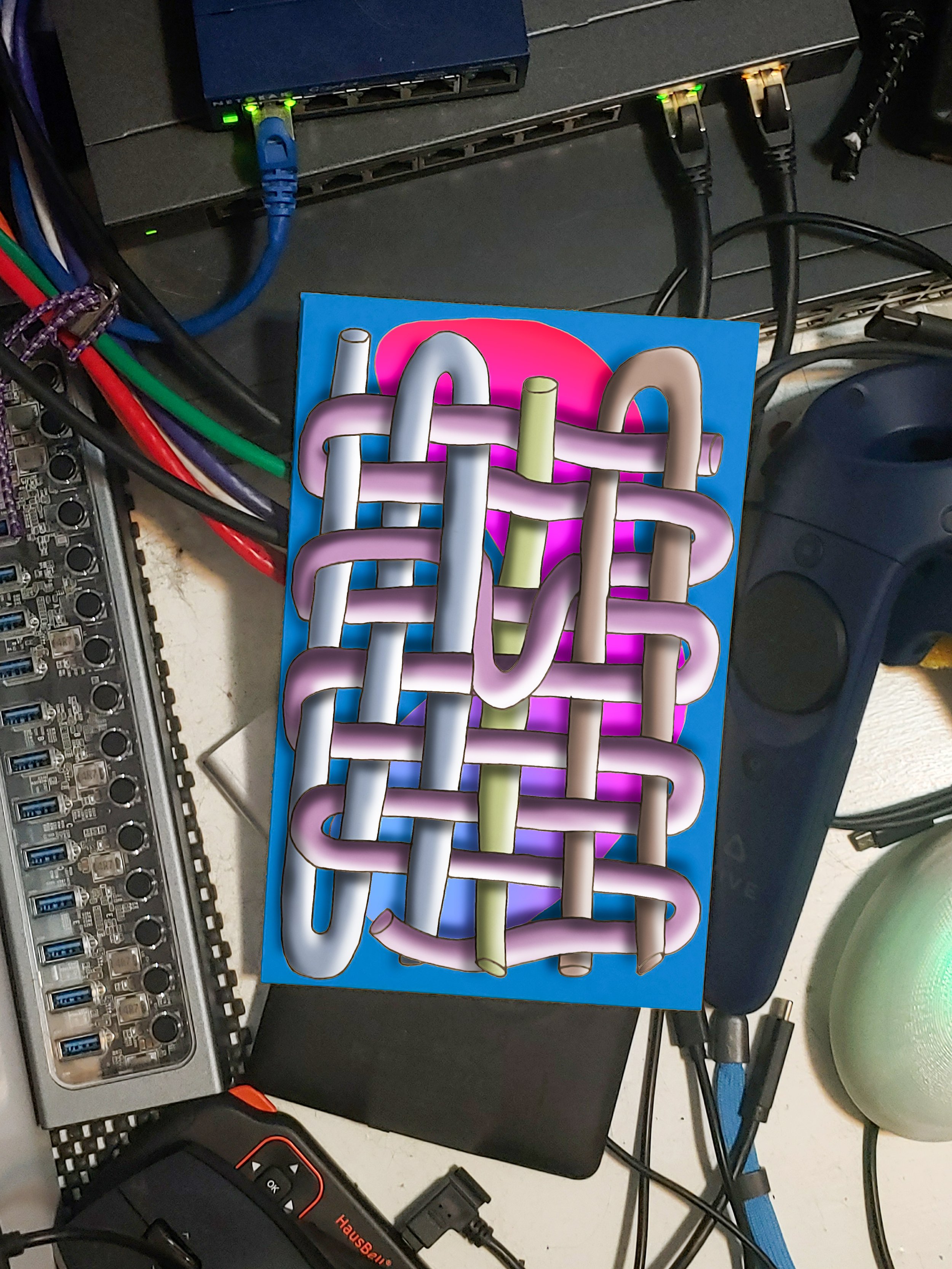

That last direction, drawing the same thing 50 times, is the one I used for Making the Bed. The process was pretty simple. The first bed was just a pillow, a platform, and four legs. The next one had drawers underneath, so fancy. Then came round beds and four posters and cribs and bunk beds and by 10 I had completely run out of bed ideas. The idea of beds expanded to places that we sleep, like homeless encampments and fire escapes and jail cells, and places other animals sleep too, like nests and burrows. One bed just referenced migraines, something that happens frequently in my bed. But then I was out of ideas again and I turned to historical research to keep me going. Turns out the first beds were just piles of wool and straw but it wasn’t until the invention of the platform off the ground that beds benefits (less bugs and rats) really kicked in.

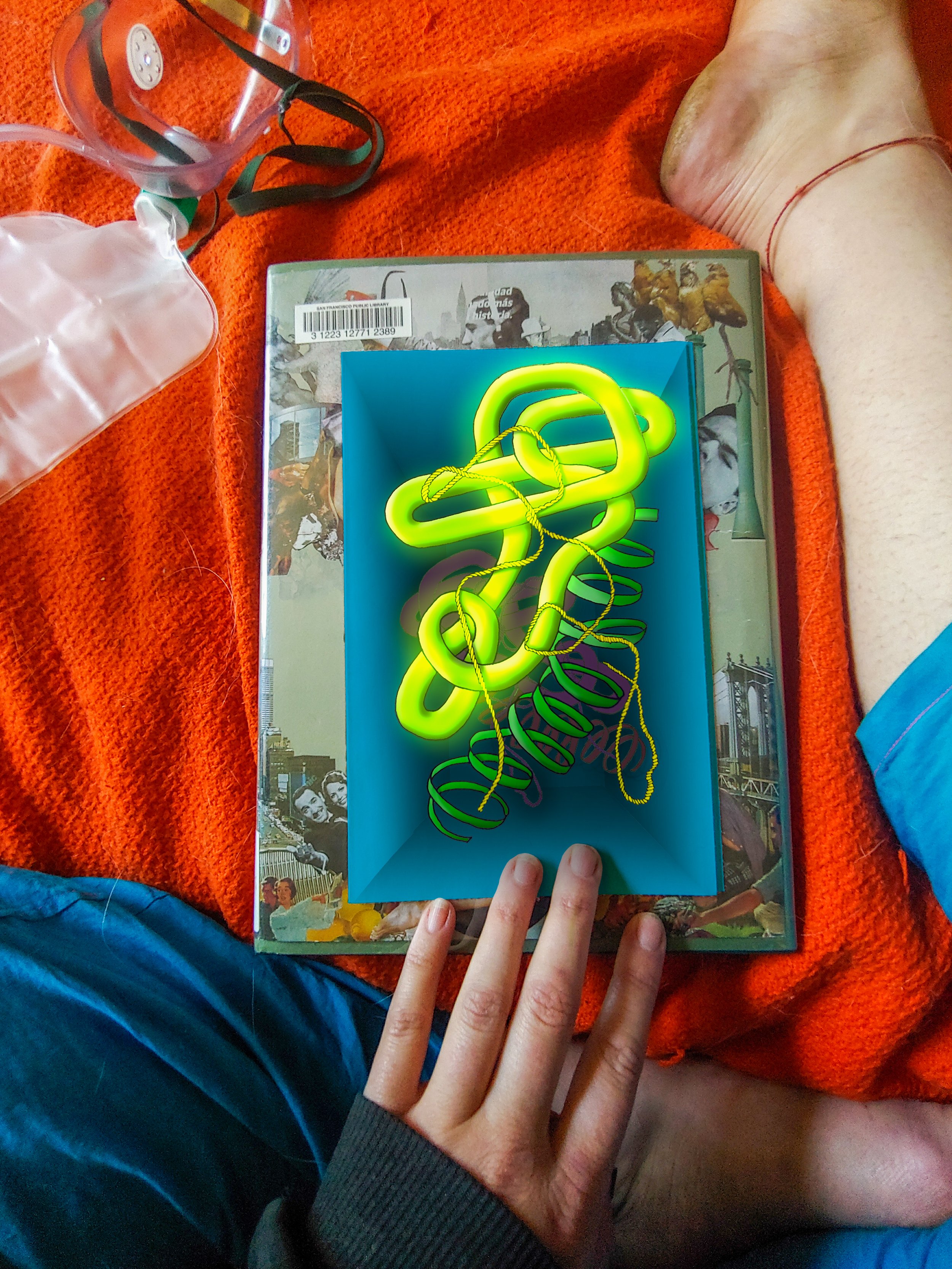

Then I went off an a metaphors and fairytales tangent making beds for the stories of Princess and the Pea and Goldilocks and the Three Bears as well as the sayings “Sleeps with the fishes” and “Dirt nap”. And eventually, in the home stretch, I realized I could make the beds any size I wanted and started designing the beds to be interesting to lay down in at life size. The layout of the final space: the mini map, the teleportation, the detailed larger versions, and the secret teleportation objects, all came out of that late stage realization.

That late epiphany about scale (a topic VR seems always to loop around back too) reveals one of the clearest advantages of the medium.

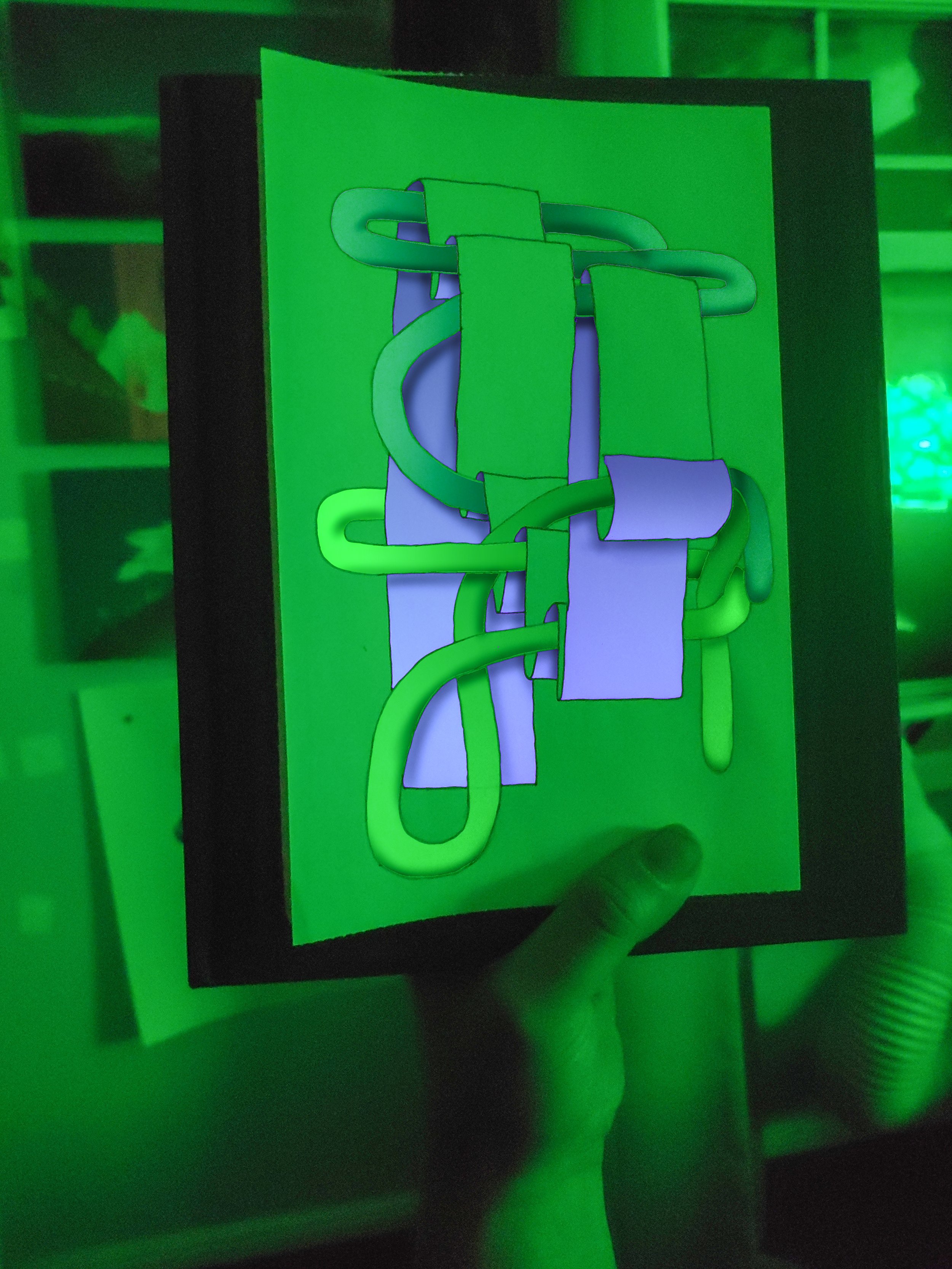

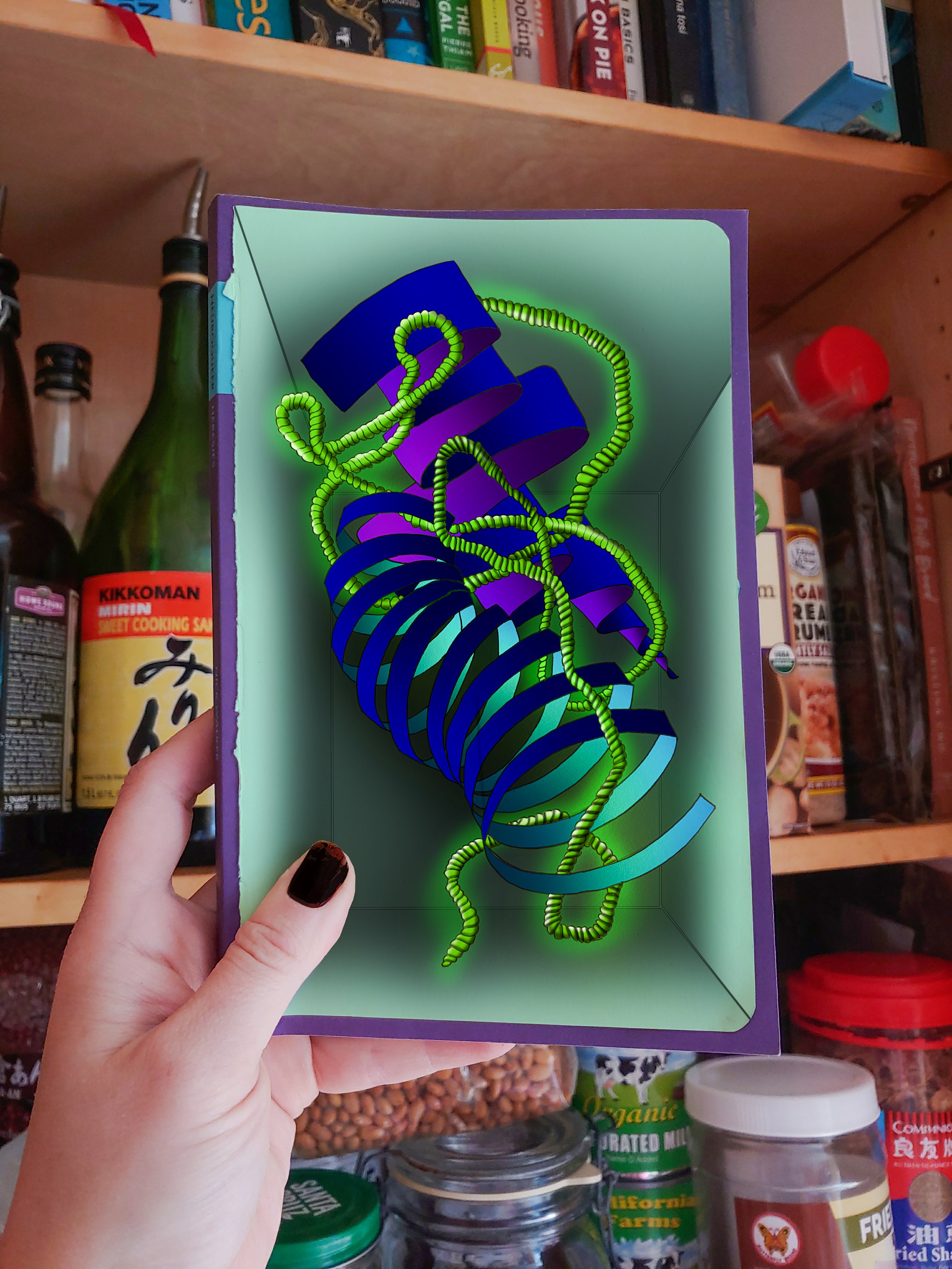

I started this project standing but at some point over the 30-40 hours it took to complete I took to sitting on the floor legs crossed meditation style or stretched out in a Y. It saved energy while still making it easy to maneuver around the space by sliding on my butt. I found my arms could work for long hours in what I have taken to calling the ‘hug range’: that empty space between your arms when you pretend to hug a large beach ball. I would on occasion reach out beyond the hug range to grab or place something but keeping my shoulder blades down my back with my elbows close in to my ribs let me work for longer.

(Side note: I have noticed that I prefer not wearing over the ear headphones while doing this work because the social hum of the lab makes the headset feel less isolating. I’m sure Chaim and Robert and Dan, my neighbors at HARC, can attest to the fact that I look ridiculous at best sprawled on the floor next to them all day with a giant black mask strapped to my head, flailing at the air with two black donuts on sticks, all while wearing an adult onesie I made myself.)

But satisfying my need to work in the hug range (a delightfully human need) also means that, at least initially, every bed had to fit within that small physical range. I made less detailed overviews as sketches. Then I scaled up the sketches and worked on them at a new level of detail. The difference here is that the same motor schema, hold up wait a minute:

Motor schema are a idea I am getting from George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s, 1999, Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and Its Challenge to Western Thought. (Hit up page 77 for a more through introduction) A motor schema is a set of movements by which I interact with a basic level category of object like a car. When the motor schema for the use of two objects varies beyond a certain threshold we put the objects in different categories: car and boat for example. But if their motor schema maintains a general similarity (steering wheel, analogue acceleration etc) we group them under an umbrella term: vehicle. Motor schema variation is one way the body creates knowledge, how it categorizes.

So again the difference here is that the same motor schema I used create the miniatures, was used to create detail on the life sized versions as well. My body is thus categorizing those two levels of zoom as the same (or at least similar) tools. You might be used to that kind of motor schema flexibility in say Maya where zoom lets us use similar finger motions to manipulate at different scales but those are symbolic, abstract interactions via the interface of the keyboard and mouse. It feels completely different to have motor schema flexibility for the distance my actual hand is moving through actual space.

Making the Bed is open to explore via Anyland just go to areas and search for “MAKING THE BED”